February 22, 2018-July 1, 2018

American Puppet Modernism: The Early 20th Century

New energies, ideas, technologies, and cultural contexts marked United States puppetry in the first half of the 20th century. European marionette and hand puppet traditions had proliferated across the country for four centuries, and by the early 1900s, two new ideas emerged: that puppetry was an ideal form for children’s education and entertainment; and that puppetry could be an ideal way to represent modern questions of culture, identity, and politics. This combination produced American puppet modernism.

The early 20th-century world considered the United States a dynamic engine of progress. American puppeteers embraced this dynamism in a variety of ways, taking advantage of new technologies of transportation, engineering, and communication as they toured across the country, invented such wonders as giant inflatable puppets, and figured out how puppets worked best with film and television.

In addition to European forms, American puppet modernists began to recognize and utilize Asian rod-puppet and shadow-puppet traditions, and developed an understanding of puppetry as a global tradition. Daring puppet experiments of the European avant-garde inspired expatriate artists such as Gertrude Stein and Alexander Calder to pursue similar projects when they returned home.

Modernist puppeteers also realized puppetry as a strong and clear way to share political, social, and cultural ideas. Immigrant artists in New York City represented Yiddish culture and contemporary politics; and as union struggles and the threat of fascism emerged in the 1920s and 30s, giant puppets in the streets and hand puppets in booth stages sounded alarms.

Political Puppetry

Wherever they emerge in societies around the globe, puppets have played a central role as commentators—most often satirical!—on social and political life. Modern political developments in the early 20th century inspired artists in the United States to use puppets to convey political ideas—an active counterpart to the equally effective use of puppets in advertising. Puppets were employed by activist puppeteers to support unionizing efforts and, as 20th-century politics evolved, to oppose fascism. Activist puppeteers used a variety of forms ranging from agit-prop hand-puppet shows to cantastorias (picture performances) and giant puppets for street demonstrations in the 1920s and 30s. In New York City, the Modicut Puppet Theater combined its sharp political satire with comic visions of Jewish life on the Lower East Side, all in Yiddish.

The Depression-era Federal Theatre Project was created to put America’s theater community back to work, and it included hundreds of puppeteers across the country. Federal Theatre Project puppet units were created across the country, and included many of the artists whose work is here on display. Ralph Chessé, who was state director of the California FTP puppetry division, wrote that “Federal Theatre gave me a chance to show that marionettes can be very high-class adult entertainment.”

Three Workers

Adolf Hitler

Benito Mussolini

Neville Chamberlain

Albert Einstein

Irving and Minna Reizes

From the Reizes Collection of the Ballard Institute

Donated by Rani Cochran and David Reizes

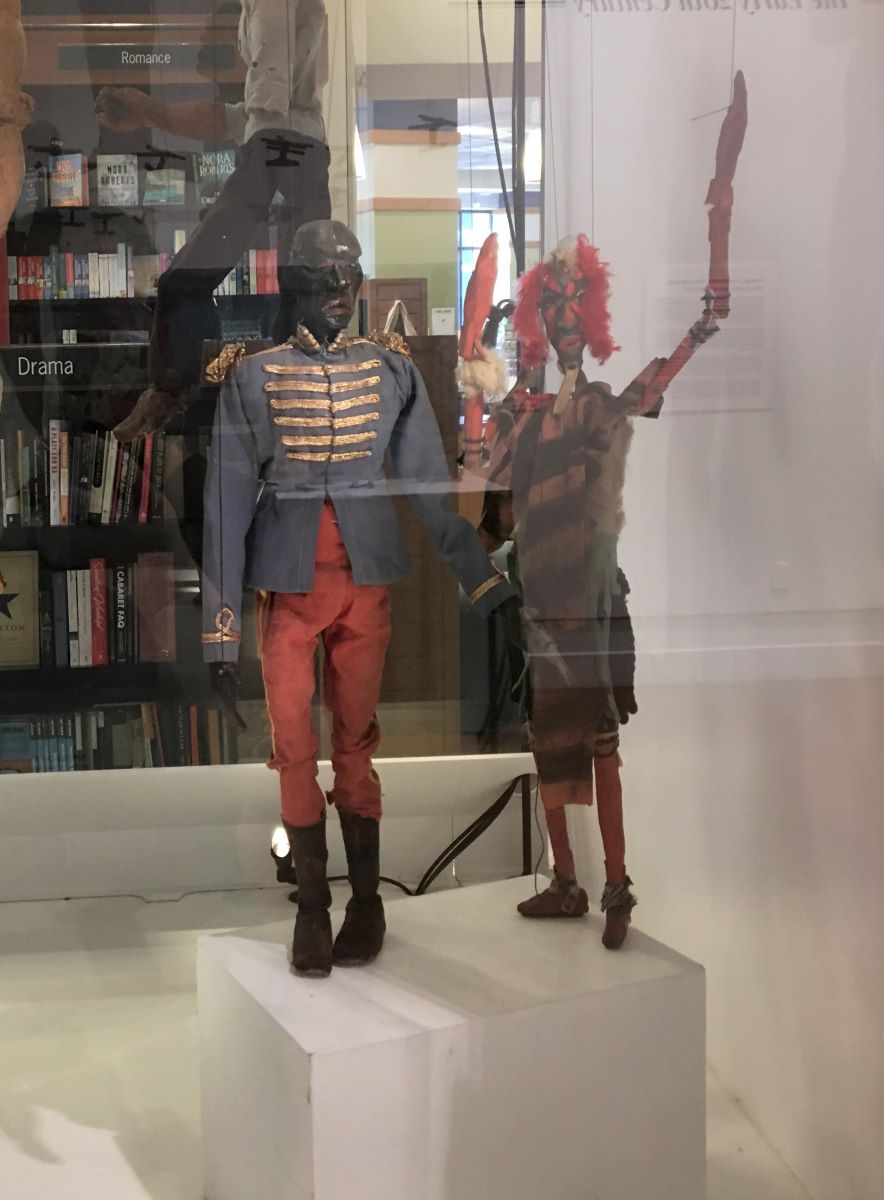

Irving Reizes (1911-2006) was part of the Suzari Marionette troupe (the first syllable of his last name was the “ri” of “Suzari”), which performed more mainstream touring shows such as Pinocchio and Peter and the Wolf in the New York City area as part of the booming puppet revival there. However, Reizes and his wife Minna (née Saltzman, 1911-1995) were also active in the labor movement, and performed political hand-puppet shows “up and down the Eastern Seaboard”, as their daughter Rani Cochran puts it, from 1936 to 1941 as part of anti-fascist, anti-Nazi activism opposed to the “America First” isolationist movement led by Charles Lindbergh and Henry Ford. Irving Reizes made the hands and heads of the puppets, while Minna Reizes created the costumes.

Old Woman

Dancing Rabbi

Mahatma Gandhi

Herbert Hoover

Hitler

Zuni Maud and Yosl Cutler, Modicut Puppet Theatre

1925-1933

From the Collection of David and Audrey Buchholz

Zuni Maud (1891-1956) and Yosl Cutler (1896-1934), immigrated to New York City from eastern Europe in time to be part of the city's 1920s and 30s puppet renaissance. Both graphic artists and political satirists, Maud and Cutler created Modicut Puppet Theater in 1925, performing such shows as Der Magid (The Itinerant Preacher) and Akhashveyrush (a Purim shpil) based on Jewish folklore. With onset of the Depression they produced more political work, such as a hand-puppet satire of The Dybbuk, making them popular with intellectuals and general audiences alike, and winng critical acclaim from the Yiddish press.

Modicut also performed in Jewish schools and workers’ clubs around New York and in 1929 toured Europe, where they were seen as exciting examples of American Yiddish modernism. They disbanded in 1933 for reasons that are not clear, and Cutler died in a car crash en route to Hollywood. Maud continued to perform live and on television.

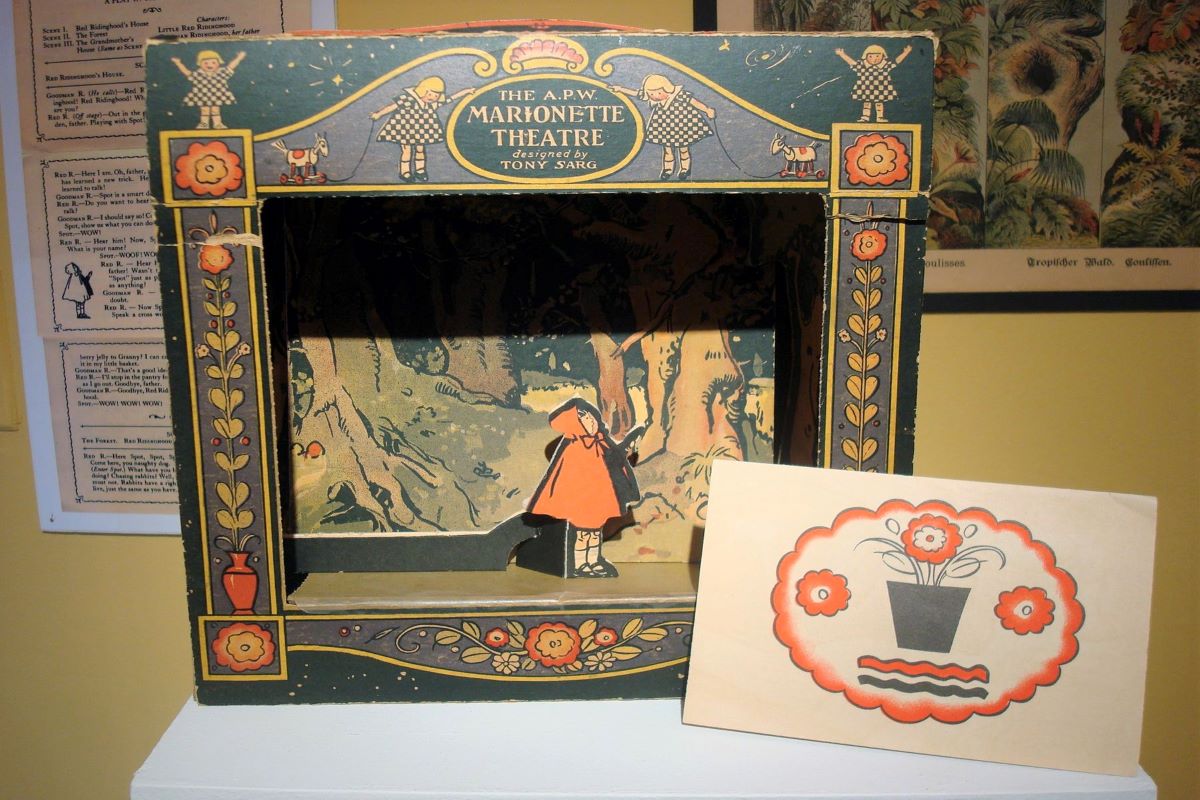

Travelling Shows: Puppets on the Road

Entrepreneur, puppeteer, and visual artist Tony Sarg created the template for the 20th-century travelling puppet theater. Basing his techniques on the classic marionette shows of Thomas Holden’s London-based company, Sarg brought puppet theater of high artistry to New York City and then to venues across the U.S. While he was well aware of the Little Theater Movement’s experiments, Sarg stuck to such shows as Jack and the Beanstalk, Treasure Island, Alice in Wonderland, and other popular fare. Sarg soon employed multiple companies which traversed the country performing his productions, and many of Sarg’s puppeteers, including Lilian Owen Thompson, Sue Hastings, Bil Baird, Hazelle Rollins, and Rufus and Margo Rose, eventually struck out on their own.

Two, three, or four puppeteers could make a living by touring and performing marionette or hand-puppet shows regionally or across the U.S. Such couples as Rufus and Margo Rose, Frank and Elizabeth Haines, Martin and Olga Stevens created shows with collapsible stages that could fit into a truck or automobile trailer and, taking advantage of the growing highway system, develop their own touring circuit.

Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future

Marley’s Ghost

Scrooge

Tiny Tim

A Christmas Carol, after Charles Dickens

Frank and Elizabeth Haines

1937

Frank and Elizabeth Haines began working as puppeteers in the early days of the Depression. Frank’s wood-carving talents and Elizabeth’s costuming and playwriting skills made them one of the most renowned marionettes troupes in the Northeast. Based in the Philadelphia area, the Haines created a variety of productions for children--including The Gingham Dog and the Calico Cat (1931), The Three Bears (1932), The Three Little Pigs (1932), Cinderella (1932), Hansel and Gretel (1933), and The Bremen Musicians (1938)--as well as shows for adults--Old Fashioned Amateur Night (1937), The Chinese Nightingale (1941), Coffee Cantata, and The Connecticut Yankee--which they performed in schools and other venues across the Eastern Seaboard from the 1930s to the 1960s. They premiered A Christmas Carol at the North Baptist Church in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania on December 30, 1937.

Huntsman

The Queen

Magic Mirror

Snow White

Three Dwarfs

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

Rufus and Margo Rose

1937

Puppeteers Rufus and Margo Rose were the leading husband-and-wife puppeteer team in the United States from the 1920s through the 1950s. They met in 1928 while members of Tony Sarg’s puppet company, where they learned the design and performance traditions of European-style string puppet. They married in 1930 and a year later formed the Rufus Rose Marionettes. The couple toured across the United States for nearly two decades, booking shows despite the hardships of the Great Depression. The Roses' national touring productions included The Variety Show (1931), Pinocchio (1934), Snow White (1937), Treasure Island (1937), and Rip Van Winkle (1941). Difficulties brought on by the Second World War caused the Roses to put their marionette touring on hold in 1942.

The Roses began working in film in 1938 with Jerry Pulls the Strings, and in the 1950s performed marionettes for the NBC children’s show Howdy Doody and produced their own television productions such as The Blue Fairy (1958).

Art as Object Performance: Socrate

Avant-garde puppetry flourished in early 20th-century Europe, but did not enjoy a similar notoriety in the U.S. Despite Little Theater Movement inspirations, radical experiments were rare. In 1931 Remo Bufano designed giant marionettes for Igor Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. Five years later sculptor Alexander Calder designed simple geometric moving sculptures to complement Erik Satie’s 1919 symphonic drama Socrate, for performances in Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.

The Atheneum’s director, Arthur “Chick” Austin, had long labored to make Hartford a center of modern art, and in 1934 presented the groundbreaking Virgil Thomson/Gertrude Stein opera Four Saints in Three Acts. And Alexander Calder had spent the late 1920s and early 30s in Paris soaking up the rich variety of avant-garde art and performance being produced by such artists, dancers, musicians and writers as Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, Jean Cocteau, Satie, and the Ballets Suédois. To produce Socrate--”a ballet danced by shapes and colors” (as historian Eugene R. Gaddis put it)--made total sense to Austin and Calder. But for Hartford and the rest of the country, it was an entirely new conception of how music and objects could combine. In 1976 conductor Joel Thome, with Calder’s blessing, re-created the artist’s moving sculptures for Socrate, which was performed the following year, after Calder’s sudden death, in sold-out shows at the Beacon Theatre.

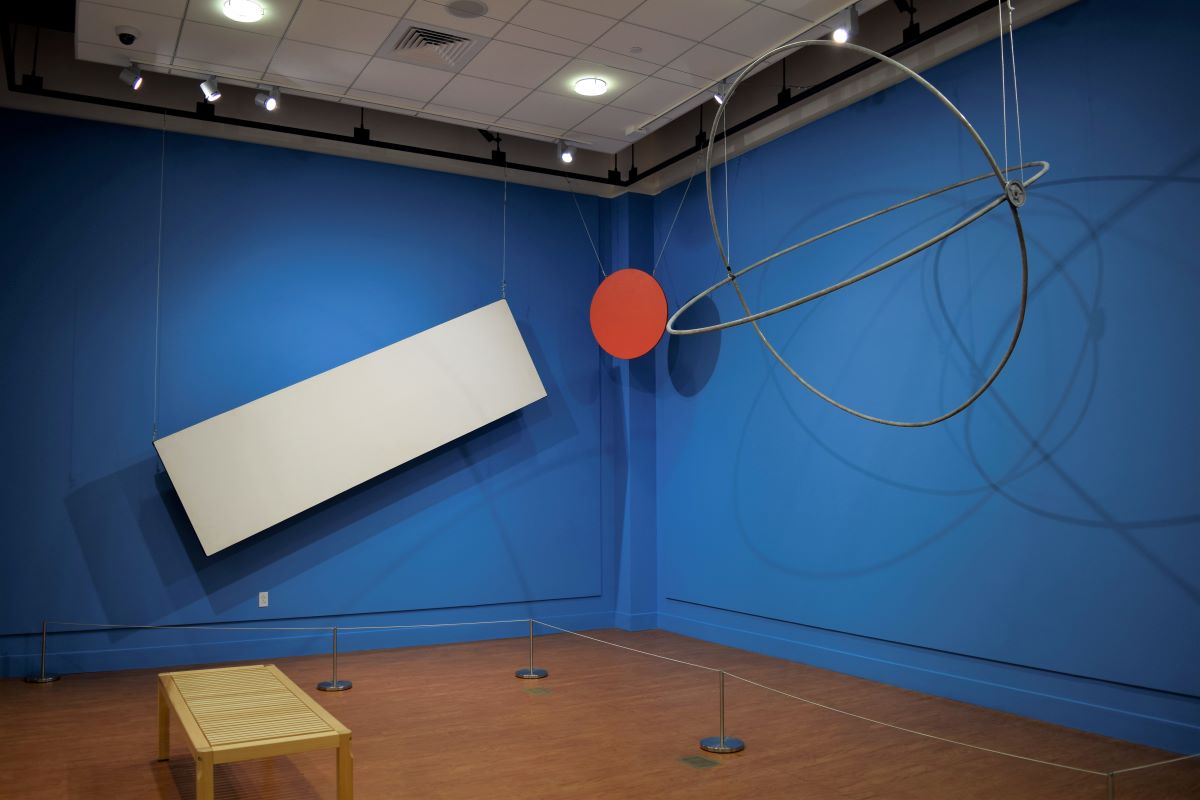

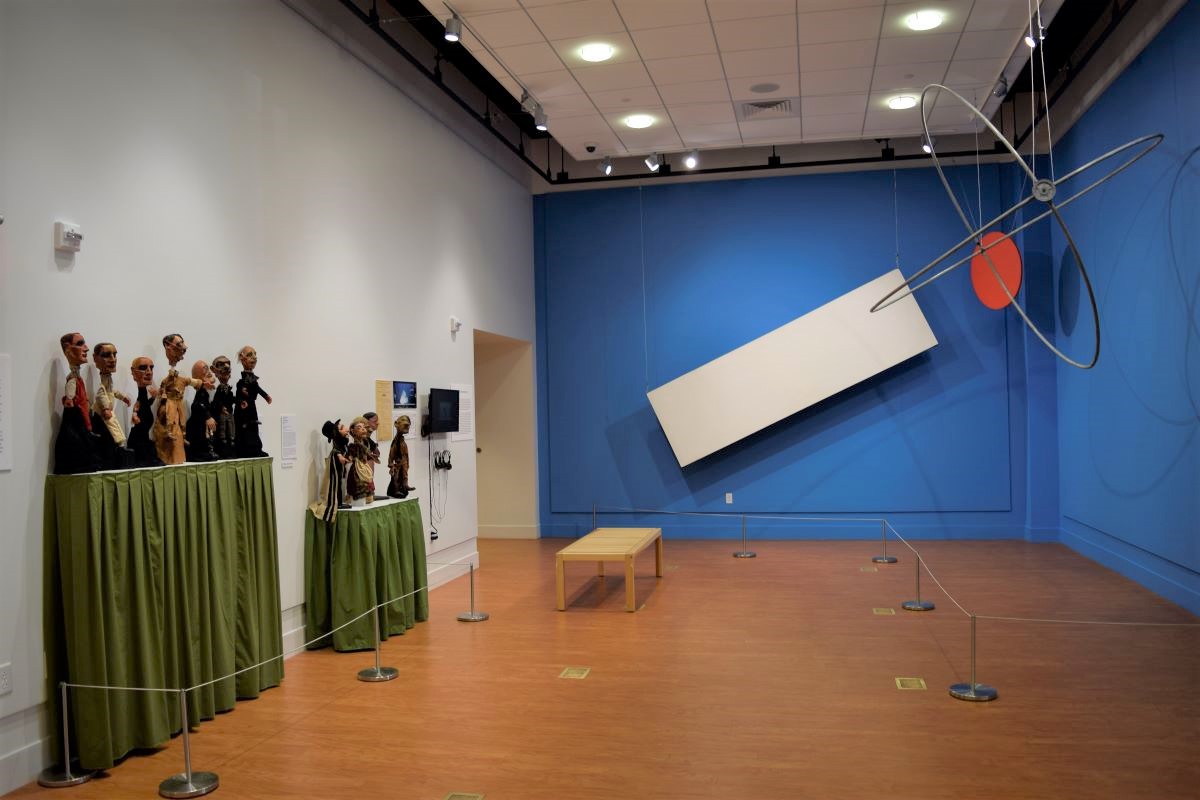

White Rectangle

Red Disc

Steel Hoops

Socrate, by Erik Satie

Alexander Calder

Reconstructed in 1976 after 1936 originals

From the collection of Joel Thome

Erik Satie’s 1919 “symphonic drama in three parts” is based on three texts by Plato about the great Greek philosopher Socrates, and is written for two voices and a small orchestra. Inspired by the radical puppet and performing object experiments he had witnessed in Paris, and by the possibilities of object performance he had explored with the wire puppets of his miniature Cirque Calder (1926) Alexander Calder designed these three geometric sculptures to be the central performers in his 1936 production for The First Hartford Festival at the Wadsworth Atheneum. “Why not plastic forms in motion?” Calder asked in an essay from the 1920s. “Not simple translatory or rotary motion, but several motions of different types, speeds and amplitudes composing to make a resultant whole. Just as one can compose colors, or forms, so one can compose motions.” These inspirations led Calder to invent his famous mobiles, but also to create stage productions with performing objects such as the ground-breaking Socrate. These reconstructions were recreated with Calder’s approval for a 1977 performance of Socrate produced by Joel Thome, Director of the Orchestra of Our Time, as part of the National Tribute to Alexander Calder at the Beacon Theatre in New York.

Puppetry as Modern Theater: Marjorie Batchelder

Marjorie Batchelder (1903-1997) stands out as a particularly strong and prescient modern puppeteer. An Illinois native, she studied teaching at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago in the 1920s, and then pursued puppetry for her M.A. (1934) and Ph.D. (1942) degrees from Ohio State University. Batchelder’s puppetry interests were deep and wide-ranging. Influenced by the Little Theater Movement, she created puppet plays for adults such as Doctor Faust (1932) and Aristophanes’ The Birds (1934) as well as Maurice Maeterlinck’s Death of Tintagiles (1937), and Edward Gordon Craig’s Mr. Fish and Mrs. Bones (1939). Entirely adventuresome, she experimented with all forms of puppetry, including rod puppets, whose roots she found in Indonesian wayang golek as well as in European forms. Together with the equally visionary puppeteer Paul McPharlin, she co-organized the first puppetry festival in the United States, an essential nationwide gathering of puppeteers in 1936 that soon led to the founding of the Puppeteers of America. Batchelder married McPharlin shortly before he died in 1949. She was a prolific writer, producing Rod-Puppets and the Human Theatre and The Puppet Theatre Handbook (both in 1947), the latter of which Jim Henson turned to when he wanted to teach himself how to become a puppeteer. She moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico in the 1950s, and in the 1960s traveled widely, researching socialist puppet trends in eastern Europe, and teaching puppetry in India. In 1969 she published a revised and updated version of her husband’s Puppet Theatre in America, which to this day is the most comprehensive history of the form as it has developed in the United States.

Chorus of Birds

Hoopoe, King of the Birds

Sacrificial Goat

Euelpides

Iris

Poseidon

Meton

Prometheus

Hercules

Pisthetaerus

The Birds, by Aristophanes

Marjorie Batchelder McPharlin

1934

Marjorie Batchelder created her version of Aristophanes’ classic comedy for her M.A. degree at Ohio State University. The story features a flock of birds who create a utopian city in the sky which soon out-rivals the power of the Greek gods, but also satirizes the political and social life of Athens.

In describing the production Batchelder wrote “[t]he bodies and hands were carved from cypress wood; the costumes followed Greek fashions of the period, and the faces were made as masks. A special stage, with a double bridge was constructed, and music was arranged by Beatrice Perham, then on the OSU staff.”