October 17, 2019-February 9, 2020

Curator's Statement

I have spent the last ten years living with, thinking about, and working with traditional Chinese shadow puppetry and its puppeteers as they witness the shift of their form from vital community practice to preserved heritage. When I began my first apprenticeship in Huaxian, Shaanxi Province in 2008, my personal perspective on preservation and material performance was preoccupied with words like “authentic” and “real.” But over the years, as I worked closely with shadow puppeteers throughout nine provinces, their own questioning has led me to larger questions of why and how we work to continue a performance form and what is lost when there is no one left to carry on the practice.

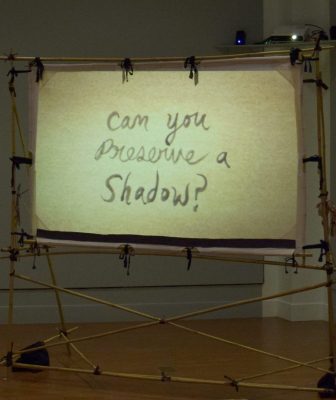

This exhibition shies away from a historic presentation and instead uses artfully hung artifacts, ethnographic video, and interactive prompts to explore the central question that drives my research: can you preserve a shadow? The main concern of the many shadow puppeteers I have worked with has not been preservation, but the passage of the practice from one generation to the next; for without human animation and interaction the shadow is truly immaterial.

– Annie Katsura Rollins

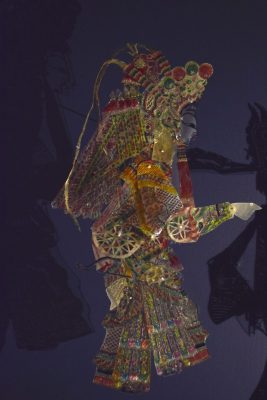

The old and the new—what accumulated life do the puppets carry with them into their new life as artifacts?

Left: Mu Guiying, Woman Warrior, by Hebei province master Lu Fuzeng. Middle: unknown artist, dated early 1900s, from the province of Gansu (Northwestern China). Right: Tang dynasty emperor, dated early 2000s, by Shaanxi province master Wangyan, one of the few women to be working at the master level in China.

Are the hanging figures more lifelike or more lifeless than their shadows?

Left to Right:

Set 1: Mounted figures by Gao Qingwang, Gansu Province

Set 2: Assorted women shadow puppets by Liu Yongzhou, Yunnan Province

Set 3: Assorted puppets and puppet heads by the Lu Family makers, Hebei Province

Set 4: Assorted puppets by Wei Jinquan, Shaanxi Province